Of

course, everybody has heard of Bucktown. That's where the canaries

bark at bulldogs, little girls in kindergarten sing bass and their

pappy shaves with a blowtorch. Some of society's blue bloods still

remember when their ancestors crossed the Chicago river from Goose

Island and started to pioneer Bucktown.

Throwing things seem an inherent trait among Bucktown's citizens. Stroll through any alley any time and you will observe some housewife heaving a can of gooey garbage from the third story back porch. If the garbage goes over the fence into the alley, the kids drive another spike into the kitchen wall plaster to record the bull's eye.

The southern boundary of Bucktown is a large automobile parking lot called Armitage Avenue, where all the reliefers park their cars.

Throwing things seem an inherent trait among Bucktown's citizens. Stroll through any alley any time and you will observe some housewife heaving a can of gooey garbage from the third story back porch. If the garbage goes over the fence into the alley, the kids drive another spike into the kitchen wall plaster to record the bull's eye.

The southern boundary of Bucktown is a large automobile parking lot called Armitage Avenue, where all the reliefers park their cars.

John Fisher Letter to

Chgo Tribune Nov 1940

To be fair, Mr. Fisher

didn't live in Bucktown, according to the census he lived on the west

side of Western in what some now call West Bucktown.

This was only the second mention of Bucktown in the press. The first was in 1898, about the price of bread, but that was a different Bucktown.

The original Bucktown was what we would now call Noble Square. It's that Bucktown that Mrs. Henry Hartjen opines on in 1953 when recalling her childhood days around Noble and Division Sts. “Our neighborhood was near a place called Bucktown”.

This was only the second mention of Bucktown in the press. The first was in 1898, about the price of bread, but that was a different Bucktown.

The original Bucktown was what we would now call Noble Square. It's that Bucktown that Mrs. Henry Hartjen opines on in 1953 when recalling her childhood days around Noble and Division Sts. “Our neighborhood was near a place called Bucktown”.

It's that Bucktown that

Nelson Algren refers to in 1947's Never Come Morning, when he says

Lefty “looks a good deal like all the other young toughs

around Bucktown”

It's that Bucktown that

a machinist and putter maker in Schiller Park named Louis Malik

talked about in 1969 when he says he came from the old Bucktown area

of Chicago, around Milwaukee and Augusta.

And it's probably that

Bucktown that the story about the residents keeping dairy goats comes

from.

The area around Armitage wasn't called Bucktown until the 1920's. My mother lived above her father's (Vincent Bielanski) bakery at 2059 N. Oakley at that time. To her, Bucktown's boundaries were Damen, Western, Armitage and Fullerton. She also thought the dairy goat thing was the funniest thing she ever heard. “Milk was cheap as dirt” she said, “the only goats around there were in back of Roman Bruszkiewicz's butcher shop, next to St. Hedwig's.” She used to play with them when she went over there to trade bread and kolacz for smoked sausage.

These boundaries remained the same for the next fifty years.

In October of '76 the Trib writes:

The area around Armitage wasn't called Bucktown until the 1920's. My mother lived above her father's (Vincent Bielanski) bakery at 2059 N. Oakley at that time. To her, Bucktown's boundaries were Damen, Western, Armitage and Fullerton. She also thought the dairy goat thing was the funniest thing she ever heard. “Milk was cheap as dirt” she said, “the only goats around there were in back of Roman Bruszkiewicz's butcher shop, next to St. Hedwig's.” She used to play with them when she went over there to trade bread and kolacz for smoked sausage.

These boundaries remained the same for the next fifty years.

In October of '76 the Trib writes:

In May of '79 it

reiterates:

So when did it start to

expand?

In the summer of 1971 a group of citizens formerly called the St Hedwig's-Pulaski Community Organization met at Holstein Park and renamed themselves the Triangle Community Organization. This was the forerunner of the Bucktown Community Organization. At this stage Bucktown was just part of the area they represented. It wasn't until 1983 that the notion of branding the larger area as Bucktown crossed their minds.

In 1983 they published a pamphlet called “The Triangle Community Organization welcomes you to Bucktown” in which they declare,

“Bucktown is three miles northwest of Chicago's Loop. Between Fullerton, Armitage, the Kennedy Expressway and Western...”

In the summer of 1971 a group of citizens formerly called the St Hedwig's-Pulaski Community Organization met at Holstein Park and renamed themselves the Triangle Community Organization. This was the forerunner of the Bucktown Community Organization. At this stage Bucktown was just part of the area they represented. It wasn't until 1983 that the notion of branding the larger area as Bucktown crossed their minds.

In 1983 they published a pamphlet called “The Triangle Community Organization welcomes you to Bucktown” in which they declare,

“Bucktown is three miles northwest of Chicago's Loop. Between Fullerton, Armitage, the Kennedy Expressway and Western...”

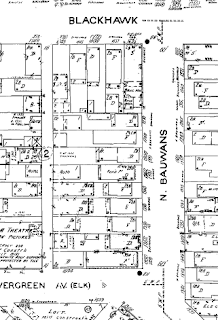

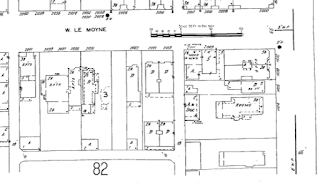

They even included this

convenient map.

This branding paid off.

The name was picked up by realtors looking for someplace to hawk and

it was soon applied to every thing down to the Milwaukee road tracks

at Bloomingdale

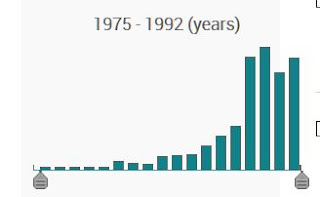

Bucktown, went from a

place never advertised before 1978 to the hot neighborhood DuJour.

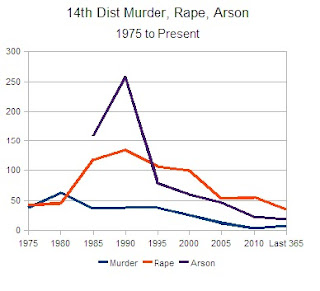

But in 1988 a real estate developer by the name of Ron Gan bought a tract of land at Wabansia and Paulina from the Archdiocese. It had been the Church of the Annunciation and its school. At one time it was the Irish church in the neighborhood but it had been closed for a decade.

Ben Joravsky interviewed Gan for a Reader article that year. Ben writes:

“Gan is the creative type. He's an exuberant optimist, a master salesman. You say the land is actually in West Town; he says, well, boundaries are subjective, and at the very least it's close to Bucktown--which he believes has a more upscale ring to it.”

That was the day Bucktown crossed the Logan Square/West Town divide. At least as far as the realtors were concerned.

But back then, even the Bucktown Community Organization wasn't buying it. Their own web page said:

“the Bucktown area is bounded roughly by Fullerton on the north, on the east by the Kennedy Expressway, the Milwaukee Road railroad tracks on the south, and on the west by Milwaukee Avenue to Western, and Western north to Fullerton.“

At least until 2010 when in a fit of expansionism they rewrote history and changed it to:

“the Bucktown area is bounded roughly by Fullerton on the north, on the east by the Chicago River, North Ave. to the south, and on the west by Western."

And started hanging Bucktown signs south of the Logan Square border.

Why did they do this?

Who knows. Maybe they have dreams of manifest destiny. Perhaps their own lackluster commercial areas on Armitage and on Milwaukee north of Bloomingdale were proving to be an embarrassment.

But,

If I was Noble Square, I'd keep my back gate locked.

Paul K. Dickman