A recent article about anti-gentrification forces in Pilsen contained the this statement.

As a Wicker Parker, I freely admit that we chose the path of gentrification, but I am tired of being the poster child for a narrative about people being displaced by Yuppies and Hipsters.

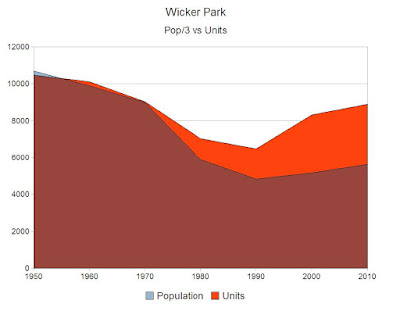

This narrative is usually accompanied by a graph like this.

It seem to show that Hispanics, after being displaced from Lincoln Park in the 60s, migrated to Wicker Park. Which grew to a predominantly Latino neighborhood, only to have them displaced again by Yuppies in the 90s.

Technically it is true (except for the part about growing) but it doesn't tell the whole story.

I have spent a lot of time pouring over census records of the 8 tracts that make up Wicker Park and here's a chart of its Hispanic population count.

You'll notice that the numbers jump in 1970 and have declined ever since.

There is no precipitous drop in the 90s. In fact the decline is so close to a straight line that no evidence of any period of displacement can be found.

Back then, Wicker Park was a slum. It was that way already in the 1960s and it was apparent to the incoming Hispanic population. No sooner did they get here, than they started to leave.

Here's a chart comparing the change in each group's populations between each census.

The period of Hispanic dominance of the population came not from the growth of that group, they were actually declining in numbers. Instead it came from the fact that everyone else was leaving faster.

That ratio switched in the 1980s.

Paul K. Dickman

Monday, December 14, 2015

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

Make no little plans 6, Unintended consequences

Two flats

A curious thing about the 1957 zoning code is that it pretty

much made it impossible to build a two flat on a standard city lot. I have

always wondered about it. I’ve never heard anyone complain about them. The

previous code had duplex districts where such things were a matter of right.

The 57 map replaced them with R3 districts. But the text precluded

putting a two dwelling structure on one lot in those districts.

The standard city lot is 25x 125 to 25x150 or 3125 to 3500

square feet.

The Code controlled density by limiting the number of

dwelling units by the square footage of the lot.

In the case of R3 it was 2200 sq ft of lot area per dwelling

unit. As you can see, in order to build a two flat you would have to combine

two standard lots. Why would you bother? Why not just build two single family

homes?

The new code also defined the minimum lot size for each

district. I have always wondered about this as well, I mean the city was 95%

subdivided by 1957. Why would anyone think it was an issue?

As I researched these articles, I could find no enmity to

this humble dwelling. In fact I found quite the opposite. The Master plan of

residential land use of Chicago clearly stated that they expected 25%-35% of the city’s population to reside in “Two

family dwellings”.

Why were these excluded from the 1957 code? Was this just

some typo that followed us to this day?

Then I read “Building new Neighborhoods; subdivision design

and standards, 1943”.

And it became clear.

They intended to change the size of the

standard city lot.

Actually, they hoped to re-plat the bulk of the city

In their opinion 25 ft lots were too narrow, 35 ft was

marginal, 40-50 ft was preferred.

A 35x150 lot has 5250 sqft more than enough for two

dwellings.

“How’s that supposed to work.? Wouldn’t a 35ft lot line be

in the middle of someone else’s house?” you might ask.

Not if you tear them all down.

They write:

“REDEVELOPMENT OF OLD CHICAGO

The recommendations contained herein

pertaining to subdivision design and standards would apply not only to the land

now vacant but to the redevelopment of the 23 square miles of blighted and

near-blighted properties which must be rebuilt within the next generation. Thus

more than 41 square miles of land in the city would benefit from improved

standards of design and from practical specifications for residential land

improvements. Within these 41 square miles over 300,000 families could find new

home sites located in well-designed, attractive neighborhoods of good character

and environment.”

Still, that’s only 20% of the city.

In the Master Plan they defined the areas of the city as:

14.60% Blighted & Near blighted

36.31% Conservation

23.34% Stable

the remainder was either vacant or under going some kind of

development

You can see them in this map.

Notice that the only areas they have marked as “Stable” are

out in the “Bungalow Belt” where the lots are already wide.

They figured that by the time they dealt with the blight,

the “Conservation” areas would now be blighted, either through decay or by

contrast with the “Rebuilt” areas. And then they would redevelop those.

Here’s another map of future development areas.

Notice that the areas formerly tagged as “Conservation” are

now labeled “Ripe for rebuilding”

And the former “Stable” areas, now they’re tagged as “Conservation”.

Since the

future solvency and livability of our great cities depend upon removing the

cancerous blighted areas that are sapping their vitality and upon building new

model communities on the cleared sites, every device, legal and financial,

should be employed to make it economically feasible for the blighted areas to

be rebuilt by private enterprise.

The scope of this is staggering. They fully intended that

the normal process of future development, would involve taking property through

eminent domain, clearing it at government expense and redistributing it to some

connected developer who build only what the Plan Commission liked.

Luckily, this did not come to pass, but as casualty of

battle, the two flat was lost.

It needn’t be permanent though. You need only change one

character of the current zoning code to make these “as of right” in RS3 districts.

Change the Minimum Lot Area per Unit Standard for RS3 from 2500 to

1500.

This would double

the population density potential of about half the city and hopefully spur

development out in the neighborhoods where it’s needed.

Paul K. Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

These maps are courtesy of the Hathitrust Digital library, they were digitized by Google from originals in the

University of Michigan collectionSunday, September 6, 2015

Make no little plans 5, We don't want nobody nobody sent

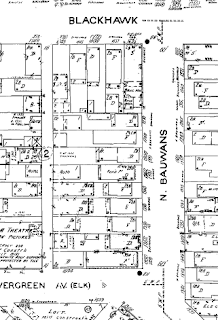

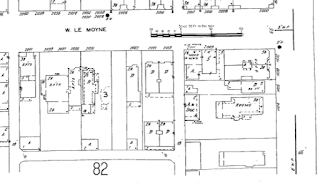

Wicker Park’s

first renewal project would also be part of its last, although the two would be

separated by almost 30 years. In ‘55 and ‘56 they demolished a couple of dozen

homes on Mautene and Bauwans (two streets now almost completely lost to

history) to make way for some parking lots where they planned to put the

new shopping center.

This was noticed by some in the community and in’56 the East

Humboldt Park Planning and Conservation Commission was formed with the intent

of getting the area designated as a “Conservation District” The Illinois Urban

Community Conservation Act of 1953 and it’s clone, the Federal Housing Act of

1954 created these districts to allow urban renewal in areas not yet classified

as slums. It freed up federal money for land acquisition as well as for repairs

to existing structures. For the city however, it would have one fatal flaw, it

required community input.

The East Humboldt commission was headed by Valentine Janicki,

a local business leader, owner of the United Novelty Mfg Co. and future

president of the Polish Alma Mater Association. He was not without his own

agenda. He had his eye on 9 sq blocks of land his commission felt need to be

cleared. He also had political aspirations, after this he would parlay his

Polish and political connections into a seat on the sanitary district, where

like all good Chicago politicos he would eventually be jailed in a sludge

hauling kickback scheme.

In ’57 Mayor Richard J. Daley, conscious of the Polish vote

appointed him to the Community Conservation Board, the group that selected

which parts of the city would become conservation areas and in ’58 East

Humboldt Park, an area bounded by Grand, Fullerton, California, and the river

(later the expressway) would gain that distinction.

Without Janicki at the helm, the East Humboldt commission

drifted into obscurity. This was probably a good thing. The Community

Conservation Act was literally designed to be co-opted by private enterprise.

It was created to allow the University

of Chicago turn Hyde Park

into their personal compound and later was used by the Southtown Planning

Association in their goal of stemming black migration in Englewood.

The city started making a conservation plan but was playing

it close to the vest. Its next two clearance projects were several houses on

Damen for rebuilding the Wicker Park

School (now Pritzker) in 1960,

And a large parcel just to the north of this for the CHA

elderly high rise project at Damen and Schiller in 62 -63

These, and announcement of several clearance projects,

including the one in what we now call Noble Square, would be a wake up call.

Several church leaders, fearing the dispersal of their flock in 1962 formed the

Northwest Community Organization (NCO), a supergroup of smaller community

organizations and a member of Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation. The

local community group at the time, The Wicker Park Neighborhood Council aligned

themselves with the NCO.

The NCO managed to get several sympathetic people appointed

to the East Humboldt Park/Near Northwest

conservation area’s Conservation Community Council (CCC), a Mayorally selected body of

local citizens with oversight and veto power over the plans and recommendations

of the Dept of Urban Renewal for each conservation area. Together they would

battle the city to a halt at every turn.

In ’67 they battled the plans for the Tuley High (now

DeDiego) expansion. Although they wanted its expansion, the Board of Ed and the

DUR wanted it to go east across Clairmont to Oakley in the land they

preemptively downzoned for a park. The NCO felt the properties to the west were

in much worse condition and better candidates for demolition.

In ’68 the NCO would convince the Board of Ed to build a new

high school inside Humboldt Park,

but that would backfire. They would have to swap land to the park department.

You guessed it, the land they wanted to swap was the same blocks, Oakley to

Leavitt, Potomac to Hirsch they had downzoned. So the

NCO fought that too. In the end the city built Clemente on the site of an old

street car barn.

In ’69 the city produced its conservation plan for the area,

a vague document with large areas slated for demolition and the NCO went

apesh!t. They wrote their own plan. the “People’s Plan” It called for only spot

removal of dilapidated buildings, no new construction over 3 stories and, the

dealbreaker, 90% of all new construction to be affordable housing.

Through their seats on the CCC they vetoed any plan that

didn’t conform to theirs.

Daley, tired of this stalemate, tried to break their power

by appointing five of his own people to the CCC in place of theirs, and the NCO

took him to court. They won and the city pretty much threw up its hands.

1973’s Chicago 21 plan did not

include anything west of Ashland.

Despite this victory NCO would play a roll in the extensive

loss of Wicker Park’s

housing. Between 1970 and 1980 we would lose 22% of all our housing units. But

few would be at the hands of the city, most were due to arson.

Two initiatives combined in ways no one could foresee.

The NCO used the Department of Buildings to put a lot of

pressure on absentee landlords, calling in inspections constantly, in some

cases forcing demolition but mostly to force landlords to repair them.

Most of Wicker Park

was redlined by the banks until the early 80s, mortgages and home improvement

loans were simply unavailable. But what most people don’t realize is that we

were redlined by insurance companies as well.

The NCO struggled to end the redlining. They had

succeeded to get the FHA to back some mortgages, but the FHA was only

interested in single family properties. They also lobbied for a high risk

insurance pool. After the King riots, they got their wish. The Fair Plan

Insurance Act made it possible for anyone to get affordable fire insurance.

Faced with a low rent property, more valuable as a vacant

lot, with the city saying, repair it or they would condemn and take it,

the availability of fire insurance led to the biggest epidemic of landlord

lightning in the city’s history.

Evergreen between Leavitt and Hoyne lost 2/3 of its

buildings and looked like a war zone.

Although the pressure from the DUR was off, Wicker

Park was still in trouble.

Housing losses continued. Between 1970 and 1980 we lost 35%

of our population and the neighborhood became a house divided. Gang struggles, ethnic tensions,

all played a role, but for our story the biggest divide was between those who

thought that rising property values were a bad thing and those who thought it

was good.

Those people, labeled gentrifiers (probably rightly) had an

idea, landmarking. It could stem the housing loss and get federal grants (in

the early years) for repairs. They formed the Old Wicker Park Committee to

lobby for this designation. In 1979 they

succeeded in getting it much of it designated a National Historic Landmark

District and set about to actively promote the neighborhood.

But battle lines were drawn in the neighborhood, one group

protested affordable housing developments, one protested market rate housing

developments. One took realtors to court for putting up “For Sale” signs, the

other sued over design issues of affordable housing projects. Neither group

could see the goals they had in common and neither could claim this as their

finest hour.

The city still had some plans up their sleeve. Determined to

get one of their plans realized, in September of 1977, Richard W. Albrecht, the

city's deputy project planning coordinator, and Robert Littlebridge, director

of economic planning for the city's department of planning, under Bilandic,

visited Sievert Electric company on Ashland and told them not to go ahead with

any expansion because the city had an interest in the area.

In October of ’79 the next mayor, Jane Byrne, announced

their plan for the “West Town

Shopping Center”. At first it

seemed to only involve the vacant Weiboldt’s building, but less than a month

later it became clear that the project involved the clearance of nearly 60

buildings.

The first developer for the project backed out when $7

million in federal loan guarantees were denied. Perhaps it was just Reagan era

austerity, but a Jan 20, 1981

memo from the U.S. Dept of Commerce said “The projected retail sales from the

applicant’s project would overwhelmingly come from the current business of

existing competitors. This project will have an adverse impact on existing

retail and office space sales”

But this didn’t stop the project. Joseph Freed stepped in

and took it over.

At the cost of approx $.25 million in 1955 dollars for the

parking lots and $3.73 million in 1980s community block grant dollars, the city

acquired and cleared the land and sold it to Freed for $635,000. Then they got him

property tax incentives worth an additional $4.9 million.

The NCO would wage a valiant effort but they would lose. It

would be their last hurrah. They continued on fighting smaller fights until

1993, when the would close up shop. Although their financial arm, the

Bickerdike Redevelopment Corp would continue to this day.

The U.S Dept of Commerce’s memo would be prophetic. Unless

you include the time when it was filled with government offices, I don’t think

the shopping center ever replaced the 275 jobs it displaced and I doubt that it

ever paid as much in taxes as the businesses and residents on the 120 parcels

it contained would have. While the rest of Wicker

Park’s shopping areas blossomed,

the south end of Milwaukee Ave

languished.

In the end, the gentrifiers would prove to be right. The

housing losses declined through the 80s and turned positive in the next decade

at a rate nearly 20 times the city average. We have put back all the housing we

had in 1970 and after 25 straight years of population growth (25% since 1990 vs

City pop -2%) we’ve put back all the people we had in 1980.

According to the 2013 estimates, the current population density

is around 25,000 ppm.

If our household size matched the city average, we’d

be in the mid 30s, right where they wanted us at the start.

Paul K. Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

Sunday, August 23, 2015

Make no little plans 4, If at first you don't succeed, try, try, try again

Land use

Their plans for land use were as subject to change as all

the others.

In general, they believed that residential uses should be

separated from any other. Industrial uses should be consolidated and separated

from dwellings by a buffer zone.

Business use would be better served by the new shopping

centers. Mixed uses (commercial with apts) were wasteful. They created low rent

apartments and only fed what they felt was an over supply of commercial space.

The 1947 zoning map shows what was allowed at the start.

The ’42 Master plan shows what they wanted for residential

uses.

Over all, they reduced the size of the residential

buildings, but planned to make up for it by increasing the amount of land

available, by reducing commercial and industrial uses and through more

efficient distribution of the land.

But they wanted to lessen crowding and intended to build an

area for a population density of about 30-35,000 people per sq mile (a

reduction from our 1940 density of 43,000).

The ’48 comprehensive plan is more specific. It has defined

the shopping areas, new parks, and buffer zones, but is has increased the land

for industry at the cost of high density residential along Milwaukee.

In 1957 they completed drafting a new zoning ordinance and completely

re-drew the map.

You can see some of their intentions. They preemptively downzoned

the area for the park between Oakley and

Leavitt. They removed most of the commercial property on Damen south of North,

and pretty much matched the Comprehensive Plan’s industrial lay out with a

little extra added in down by the Felt & Tarrant Adding Machine plant.

The notion of wide scale land clearance and redistribution had

become less realistic after the Urban Community Conservation Act of 1953 and

their plans gradually got smaller.

I apologize for my efforts on the current zoning map.

Decades of spot zoning have left it looking like a painter’s drop cloth. There

are so many, that I gave up East of Ashland.

Paul K. Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

Sunday, August 9, 2015

Make no little plans 3, If at first you don't succeed, try, try...

Streets

It is important to realize that all the things we consider

as the very model of a modern urbanist plan, things like increased transit

infrastructure, increased density near transit stations and employment centers

and walkable neighborhoods, were the cornerstones of these earlier plans as

well.

The difference was that they wanted to reinvent the

neighborhood.

To the plan commission, each neighborhood was an area

bounded by four major (1/2 mile) streets. Each neighborhood would have

sufficient grade schools for its intended population located on the interior

with a park connecting them and perhaps a neighborhood shopping center (strip

mall) on the edge.

Several neighborhoods would form a community area. Each

community area would contain sufficient high schools and a large community

shopping center at their junction.

Several communities would be bounded by the new expressways.

Ours included not just the Kennedy, but ones on California

and Grand Aves as well.

In the neighborhoods, through traffic was the nemesis of

walkability. They planned to widen the major streets to provide traffic

capacity, and interrupt the flow through the side streets with cul-de-sacs and

loops. They also felt that alleys were a waste of land and, that the rights of way of the side streets could

be reduced from a typical 66 feet down to 50 feet.

This is what they saw a model for the new neighborhood. This

one was an example they found in Columbus, Ohio.

Using this as a model this is what Wicker

Park could look like.

The parks and shopping centers are taken from the actual

plans, but more on land use in a later segment.

Their plan for the major streets varied widely. In ‘42s plan for residential land and ‘48s

preliminary comprehensive plan they were not specific, although it is a safe

bet that they hoped to widen North Avenue

to match the portion west of Western. But in 1952. their plan for the northwest

central area, went out on a limb.

They wanted North ave (currently 100’ west of Western, 66’

east) widened to 200 feet (incorporating the Humboldt Park Elevated ROW). Milwaukee

should be widened to 250 feet (currently 66’) at least as far south as Grand.

And they felt that it would be cheaper to acquire the necessary land on streets

like Damen and Racine than on Western and Ashland,

so Damen, Racine, Chicago and Armitage should be widened to 200 feet.

The extra width of North and Milwaukee

was to provide space to bury the rest of the Elevated lines. It was cheaper to

put them in a trench and that was their plan.

By 1958, they softened somewhat. A few things had happened.

For one the Humboldt Park El line closed about the time of their last plan.

Another thing that happened is that the area fought for and succeeded in

getting the “East Humboldt” area classified as a conservation area. This

curtailed widespread land clearance and increased certain forms of federal funding

for building improvement and FHA mortgages.

In a preliminary traffic study CDoT greatly reduced their

road widening goals.

Milwaukee was to

remain at 66’, North, Chicago and Damen widened to 100’ and Armitage widened to

80. They also seem to have given up on the Grand Ave Expressway, it was now

recommended to be widened to 100’.

Milwaukee,

however was not immune from further planning. In 1968 they wanted to

deemphasize the diagonal streets. They presented three possibilities for Milwaukee

between North and Division. All of them involved closing it to through traffic.

One was to tear out all the commercial and make it a residential street,

another to keep it a commercial strip, with residential infill replacing the

deteriorated structures, and finally to tear out everything, build shopping

malls at either end and turn the rest into a park.

The thing that surprised me the most, while researching

these plans, was the disdain the urban renewal planners held for the street

grid. They seemed to be of the opinion that the middle class was being driven

from the city by the unrelenting monotony of parallel streets.

Paul K, Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

Saturday, August 1, 2015

Make no little plans 2, If at first you don't succeed....

Blight

Alas, the tiny hamlet of Wicker

Park could not avoid the planners.

The city drew up a plan for us, In fact they drew up at least five official

ones. An assortment of private parties drew up their own. Some, were written as

a rebuttal to the Plan commission’s ideas, others came from well meaning

busybodies and graduate students.

A 1939 WPA sponsored survey of housing had noticed us and

its report led the city planners to label us as “Nearly blighted” in the 1942

“Master plan of residential land use”

Below is their assessment of the conditions.

Their assessment probably wasn’t far from the truth. We hadn’t

been a fashionable neighborhood since the teens the housing stock was old and

run down and packed chock full of people. But this war time, and although

refining their plan, the city didn’t go any further.

In 1952 they drew up "A plan to guide redevelopment in the northwest central area of Chicago" and once again they assessed our blight.

Add caption

You can see, the map has changed some. They separated the industrial areas (this plan had provisions for industry), the blight has moved around some, and the conservation area is much smaller. They claim the source of the data is the same 1939 survey, so I am not sure how the blight could wax and wane. Perhaps blight is in the eye of the beholder.

The city had more urgent blight to fry in Lincoln Park and Noble Sq, so it wasn’t until the late 60s that they thought about sending the dozers our way.

In 1969 they drew the “Proposed treatment areas for the East Humboldt Park, Near Northwest Area”, and once again tiny Wicker Park was on the map.

In the end, little of their plans would be built and large scale demolition would be held to a few city blocks.

Next time I’ll discuss the multiple plans for Wicker

Park’s streets.

Paul K. Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Make no little plans

In the 1950 census, Chicago

hit its peak population 3.6 million. Few realize that this last spurt of growth

was due entirely to the great migration. The African American population

increased 220,000 while the white population actually declined by about 3000.

Ok, 3000 doesn’t seem like much, but when you factor in the rate of natural

increase (birth rate – death rate) it constitutes a loss of 750,000 potential

Chicagoans.

The first thought is to put this loss down to “white

flight”, but that doesn’t hold water.

Here’s a map. It shows areas of population loss and gain

between 1940 and 1950.

The red portions show the African American communities

traced from a 1950 settlement map showing Chicago’s

various ethnic communities.

Vast losses occurred in tracts where the residents

never saw a black man.

The areas of loss have more in common with this map, showing areas of blight.

The city had been bleeding population to the suburbs for

decades. The city of 1950 was a dump. The free market had favored the slumlord

since the depression and our neighborhoods were dirty, crowded, smelly, run

down places. As soon as the streetcars crossed the city limits, people loaded

up their families and moved.

This didn’t escape the notice of the people who drew those

maps. They are from the Chicago Plan Commission’s 1942 Master plan for

residential land use.

Their plan was to bulldoze the blighted and near blighted

areas, and create mini suburbs between the half mile streets, each with its

own school and park. The side streets would be cul-de-sacs and the 1/2 miles

widened to carry all the traffic. Then, they’d plop shopping centers at the

corners.

Here’s their plan for Little Italy.

They write:

WEST SIDE REDEVELOPMENT PLAN. It is possible to create new

neighborhoods and better residential patterns near the center of Chicago

without scrapping all of the streets and utilities which exist today. This plan

for the reconstruction of a West Side Blighted area calls for the demolition of

the present obsolete buildings in order to provide much-needed open space for

parks around the schools and community centers and ample yards about the

residential buildings. Unnecessary streets would be closed to protect the

residential sections from traffic hazards, but major through streets of the

present would be retained. Heavy traffic would be confined to the

super-highways and section-line streets which form the boundaries of this community.

Organization of shopping facilities into coordinated centers with parking

facilities and access to highways would make them easily available without conflicting

with purely residential areas. Residential areas would be built up with

apartment buildings three to four-stories in height and with two-story group

houses. A moderately high population density would be achieved without crowding

of either land or people.

Unencumbered by existing utilities in undeveloped areas,

they hope to do away with the grid all together.

Here’s their idea for Scottsdale

They write:

PROPOSED PLAN FOR DEVELOPMENT OF A VACANT AREA IN SOUTHWEST

CHICAGO. Here is indicated how an area of now-vacant land comprising over

one and one-half square miles on the southwest edge of the city might be

subdivided according to the best principles of community design. Curved streets

in the interior residential portions discourage dangerous through traffic which is channelized

into the bordering super-highways. Schools placed near the centers of the five

neighborhoods are so located that small children can reach them without having

to cross major traffic arteries. A centrally located high school with an associated athletic field and

community park serves the entire community. Adjoining these facilities is a

large community shopping center, and smaller neighborhood shopping centers are

placed to serve two or more adjoining neighborhoods. The residential areas are

separated into sections of apartments, group houses, and single-family

dwellings arranged to give each type the maximum advantages of light, air, and

open space around the structures. Such a community design illustrates what

might be accomplished by creating an integrated community pattern designed to

offer the maximum advantages for living.

Apparently the city of the future would look like Elk

Grove Village.

Paul K. Dickman

These maps are courtesy of the Hathitrust Digital library, they were digitized by Google from originals in the

University of Michigan collection

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

Monday, May 25, 2015

The sky is falling

A couple of months ago, a blogger by the name of Hertz wrote a piece about Unecessary population loss in Lincoln Park. It got picked up by Crain's and splattered all over the web faster than cat pictures.

You can read it here:

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20150323/OPINION/150329972/who-would-have-guessed-that-lincoln-park-was-seeing-population-loss

or here

http://danielkayhertz.com/2015/03/16/unnecessary-population-loss-on-the-north-side-is-a-problem-for-the-whole-city/

Ordinarily I have better things to do than debunk every blowhard on the internet, but now I have developers spouting it like chapter and verse and I want to go on the record as saying "this is unadulturated BS."

He noticed a slight decline in both the population and the housing unit count for the Lincoln Park community area between the 2000 and 2010 censuses. Rather than look closer at these numbers, he took it as proof of his thesis that zoning is killing the city and now McMansionization sucking up precious dwelling units. Then he ran around like Chicken Little yelling "the sky is falling"

How big were these losses, he didn't say, but the population loss amounted to 204 people (0.3% of the pop)

Given that the city on average lost 6.9% of it's population in the same period, I'd say that's pretty darn good.

http://www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/zlup/Zoning_Main_Page/Publications/Census_2010_Community_Area_Profiles/Census_2010_and_2000_CA_Populations.pdf

The housing loss was a whopping 534 units. But when you drill down to the actual data, the bulk of this loss (over 400 units) occurred in 3 census tracts dominated by the DePaul campus who started expanding and restructuring their planned development just before 2010. Hardly gentrification and more than adequately compensated by this project:

http://www.usa.com/IL0318325002001.html

Here's a chart to illustrate the situation.

The red area indicates LP's unit count, the blue area LP's pop and the green area the city's pop (divided by 40 to bring it into scale)

Hardly the end of the world.

Certainly gentrification has consumed some units but it is a drop in the bucket and not necessarily a bad thing.

Lincoln Park is approaching the Units/mile it was designed for and now it's time to grow up. It's problem is not its unit count but its puny household size of 1.73. It's time to start procreating, maybe then they achieve a higher population density than Albany Park, a mature RS-3 district which, despite a population decline of over 10%, still manages a density 35% higher than Lincoln Park (which for the most part is zoned for densities 3 to 7 times as high).

The article also pines for the glory days of the 1950s but the author seems oblivious to the fact that in the fifties, Lincoln Park was a frickin slum. I imagine he pictures the fifties as all "Leave it to Beaver" and "Happy Days" but it wasn't, it was more like "Blackboard Jungle"

It would never have become a fashionable neighborhood until the Dept of Urban Renewal bulldozed half of it down.

Lets look at one census tract from the 1950 Census of housing.

It had 2447 DUs (it would be more now, until 1960 SROs, Residential Hotels and Rooming houses were each one DU)

300 of them had no heat

10% still used ice boxes and 5% had no refrigeration.

747 had no washroom, 337 had no running water at all.

Those were the days.

By 1970 it was down to 1700 DUs 20% of those were vacant.

You'll be happy to know that they all got running water. But 10 still used an outhouse

In 2010 it was down to 1477 DUs.

The good news is that the median rent went from $20 to $2000.

There is some kind of fantasy that Joseph and Mary are on the west side of Harlem waiting to live in Chicago but there is no room in the inn.

This notion that "if you build it they will come" is a fallacy

In reality we have about 99% of the DUs we had our peak in 1960 and the difference in household size doesn't explain the difference in population.

Except in Lincoln Park. If they got their Household size up to the current Chicago average they would have over 90,000 people living there.

You young people should be humpin' like bunnies. I don't know what the problem is, maybe you should try some candles or scented oils.

Paul K. Dickman

A kindred post for further reading

http://yochicago.com/crains-deeply-misleading-article-on-lincoln-parks-population/38674/

Saturday, May 23, 2015

No highway in the sky

You know, I can't go to a meeting, or even have a discussion, about the Bloomingdale trail (AKA The 606) without someone asking the question, "When will they extend it to the river?".

I'm here to tell ya, quit askin'.

The answer to that question is "Not in our life times."

The people building it won't tell you that. When asked, they hem and haw around it like a politician being asked about taxes.

I'm not sure why they do that. One guess is that a lot of money for alternative transportation is backing the construction and they don't want to admit that it is the bicycle version of the Amstutz Highway (AKA The road to nowhere) until they finish this part.

The problem is that on the other side of Ashland the ROW makes a grade crossing with a commuter railway. In fact with two lines of the Metra UP. On the average week day, during park hours, over 130 trains cross there. About 1 train crossing every 8 minutes. A crossing gate isn't an option.

How about a bridge? To build a bridge to clear the bi-level rail cars to ADA standards (slope of 1 in 12 and landings every 30" in rise) will require ramps around 250 feet long. The good news is that there is enough land there to do that and connect to another underused track that crosses over Clybourn and runs directly to the river.

The bad news is that they don't have the headroom.

The expressway crosses over the Bloomingdale line about 60 feet from the Metra tracks. In fact the height of the expressway bridge at this point was designed specifically to to clear the loading guage of a boxcar on the Bloomingdale line. I estimate it to be no more than 20 feet above the railbed. But that doesn't matter, the trail bridge would need at least as much structure gauge to clear the commuter line 60 feet away.

60 feet, one landing. You will have a maximum of 57 inches of headroom when you pass under the Kennedy.

You could build a bridge that rises 10 feet under the expressway, turns 90 deg, goes another 125 feet, turns 90 deg again over the tracks and does it all over on the other side. This is a lot more complicated and involves rights of way they do not own.

In some ways, a viaduct would be a better solution. It only needs to be eight or ten feet deep. That would still be above the street level so drainage would be easy. But you would need a bridge to support the rails. I can't imagine that happening without interrupting all rail traffic on those lines for at least a couple of weeks, Not bloody likely.

Getting the trail to the east side of the Metra tracks will probably cost more than all the other bridgework on the trail, and CDoT won't be doing much of it. Until a river trail runs all the way downtown, the impetus to fund such an undertaking will not exist.

Accept the 606 for what it is. A nice park, someplace to take a stroll on a sunny morning and maybe a bicycle shortcut from the "K" streets to the Metra station. But it's no highway in the sky.

Paul K. Dickman

I'm here to tell ya, quit askin'.

The answer to that question is "Not in our life times."

The people building it won't tell you that. When asked, they hem and haw around it like a politician being asked about taxes.

I'm not sure why they do that. One guess is that a lot of money for alternative transportation is backing the construction and they don't want to admit that it is the bicycle version of the Amstutz Highway (AKA The road to nowhere) until they finish this part.

The problem is that on the other side of Ashland the ROW makes a grade crossing with a commuter railway. In fact with two lines of the Metra UP. On the average week day, during park hours, over 130 trains cross there. About 1 train crossing every 8 minutes. A crossing gate isn't an option.

How about a bridge? To build a bridge to clear the bi-level rail cars to ADA standards (slope of 1 in 12 and landings every 30" in rise) will require ramps around 250 feet long. The good news is that there is enough land there to do that and connect to another underused track that crosses over Clybourn and runs directly to the river.

The bad news is that they don't have the headroom.

The expressway crosses over the Bloomingdale line about 60 feet from the Metra tracks. In fact the height of the expressway bridge at this point was designed specifically to to clear the loading guage of a boxcar on the Bloomingdale line. I estimate it to be no more than 20 feet above the railbed. But that doesn't matter, the trail bridge would need at least as much structure gauge to clear the commuter line 60 feet away.

60 feet, one landing. You will have a maximum of 57 inches of headroom when you pass under the Kennedy.

You could build a bridge that rises 10 feet under the expressway, turns 90 deg, goes another 125 feet, turns 90 deg again over the tracks and does it all over on the other side. This is a lot more complicated and involves rights of way they do not own.

In some ways, a viaduct would be a better solution. It only needs to be eight or ten feet deep. That would still be above the street level so drainage would be easy. But you would need a bridge to support the rails. I can't imagine that happening without interrupting all rail traffic on those lines for at least a couple of weeks, Not bloody likely.

Getting the trail to the east side of the Metra tracks will probably cost more than all the other bridgework on the trail, and CDoT won't be doing much of it. Until a river trail runs all the way downtown, the impetus to fund such an undertaking will not exist.

Accept the 606 for what it is. A nice park, someplace to take a stroll on a sunny morning and maybe a bicycle shortcut from the "K" streets to the Metra station. But it's no highway in the sky.

Paul K. Dickman

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Bicycle Birtherism

In Jan of 2014, The Tax Foundation published this study that showed that user fees on cars only paid 51% of road construction costs.

http://taxfoundation.org/article/gasoline-taxes-and-user-fees-pay-only-half-state-local-road-spending

This was bandied all over the Internet by the usual suspects as proof that auto-mobiles are a losing proposition and that non-drivers property taxes are subsidizing the drivers' lifestyle.

For what it's worth the original study was true, but they construed user fees pretty narrowly (MFT, tolls, licenses). That is like saying that the news stand price doesn't cover the cost of publishing magazines. Everyone knows that, like roads, other revenues makes up the bulk of their income.

In fact, the Tax foundation's previous study showed that cars only covered 1/3 of road costs because the felt that licenses and the Federal Motor Fuel Tax were not dispersed proportionately and shouldn't be called user fees.

http://taxfoundation.org/article/gasoline-taxes-and-tolls-pay-only-third-state-local-road-spending

A more in depth study from 2007 looked at a much wider range of revenue sources like sales taxes, fines and income taxes and corporate taxes from the auto and gasoline industries, and even this study showed that income and expenses were pretty close to even until you started adding intangible expenses like the wars in the Middle East.

http://ti.org/delucchiinpress.pdf

That may be how it plays in Peoria, but I'm here to tell you that's not the Chicago way.

Here in the Windy City, the auto-mobile is a major cash cow and my bona fides are as close as the city's 2015 budget.

http://chicityclerk.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2015OV.pdf

I didn't try to track the path of the MFT or the City sticker revenues to their final destinations. That would be a fools errand, and frankly I don't care how the Department of Buildings justifies 6 full time employees being funded by the Illinois motor fuel tax. My approach was simply X amount of income comes from auto-mobile related sources and Y amount is spent on maintaining the roadway.

Income sources include, State, Federal and Municipal Fuel taxes, City sticker revenues, impound fees, Fines for parking and red light/speed camera infractions and a variety of taxes on taxis, parking lots, etc,. I ignored less verifiable sources like sales taxes on gasoline and cars, and property taxes on gas stations and parking lots.

Expenses are simply the gross budgets of CDoT and Streets and San, including infrastructure and administrative costs, minus trash pickup, rat abatement and those infrastructure projects solely for pedestrian, transit or bicycling. Certainly there are other costs, like fire and police calls related to autos, but these departments benefit from the roadway as well. The Fire Dept's budget would be a lot different if they had to limit each stations range to a distance they could transport their equipment on a rickshaw. A few years ago, (to double check a private traffic study), I took a series of rush hour traffic counts on North Ave. An unexpected observation was that 10% of all vehicles and 25% of all heavy vehicles, belonged to the city. Buses, garbage trucks, police cars, Water Dept dump trucks all depend on the pavement to do their job.

But enough of that, Here are the numbers.

Expenses:

+$258,865,234 Streets and San Total budget

- $156,645,516 Less Solid waste (but including street sweeping)

+$598,286,287 CDoT Total budget

-$206,643,000 Less Bike, Transit, Pedestrian improvements

$493,863,005 Total Auto spending

Income:

$99,100,000 State MFT

$205,100,000 Vehicle tax(Sticker, towing, impound)

$188,000,000 Transportation taxes (City MFT, Garage, Taxi)

$6,400,000 Motor Vehicle Lessor Tax

$4,100,000 Municipal auto rental tax

$6,400,000 Municipal Parking

$256,000,000 Fines, Forfeitures, Penalties (auto related)

$298,800,000 Infrastructure Grants (sourced from Fed or State MFT)

$1,063,900,000 Total Income

$570,037,000 Profit

Just for perspective, top income sources listed in the Budget are:

$1,299,000,000 Airports

$1,150,400,000 Water and Sewer

$831,500,000 Property Tax Levy

So, the gross revenues collected, make the auto-mobile Chicago's 3rd highest income generator and the profits are on par with the $647,900,000 the city hopes to receive from its share of the State and local Sales taxes.

Paul K. Dickman

http://taxfoundation.org/article/gasoline-taxes-and-user-fees-pay-only-half-state-local-road-spending

This was bandied all over the Internet by the usual suspects as proof that auto-mobiles are a losing proposition and that non-drivers property taxes are subsidizing the drivers' lifestyle.

For what it's worth the original study was true, but they construed user fees pretty narrowly (MFT, tolls, licenses). That is like saying that the news stand price doesn't cover the cost of publishing magazines. Everyone knows that, like roads, other revenues makes up the bulk of their income.

In fact, the Tax foundation's previous study showed that cars only covered 1/3 of road costs because the felt that licenses and the Federal Motor Fuel Tax were not dispersed proportionately and shouldn't be called user fees.

http://taxfoundation.org/article/gasoline-taxes-and-tolls-pay-only-third-state-local-road-spending

A more in depth study from 2007 looked at a much wider range of revenue sources like sales taxes, fines and income taxes and corporate taxes from the auto and gasoline industries, and even this study showed that income and expenses were pretty close to even until you started adding intangible expenses like the wars in the Middle East.

http://ti.org/delucchiinpress.pdf

That may be how it plays in Peoria, but I'm here to tell you that's not the Chicago way.

Here in the Windy City, the auto-mobile is a major cash cow and my bona fides are as close as the city's 2015 budget.

http://chicityclerk.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2015OV.pdf

I didn't try to track the path of the MFT or the City sticker revenues to their final destinations. That would be a fools errand, and frankly I don't care how the Department of Buildings justifies 6 full time employees being funded by the Illinois motor fuel tax. My approach was simply X amount of income comes from auto-mobile related sources and Y amount is spent on maintaining the roadway.

Income sources include, State, Federal and Municipal Fuel taxes, City sticker revenues, impound fees, Fines for parking and red light/speed camera infractions and a variety of taxes on taxis, parking lots, etc,. I ignored less verifiable sources like sales taxes on gasoline and cars, and property taxes on gas stations and parking lots.

Expenses are simply the gross budgets of CDoT and Streets and San, including infrastructure and administrative costs, minus trash pickup, rat abatement and those infrastructure projects solely for pedestrian, transit or bicycling. Certainly there are other costs, like fire and police calls related to autos, but these departments benefit from the roadway as well. The Fire Dept's budget would be a lot different if they had to limit each stations range to a distance they could transport their equipment on a rickshaw. A few years ago, (to double check a private traffic study), I took a series of rush hour traffic counts on North Ave. An unexpected observation was that 10% of all vehicles and 25% of all heavy vehicles, belonged to the city. Buses, garbage trucks, police cars, Water Dept dump trucks all depend on the pavement to do their job.

But enough of that, Here are the numbers.

Expenses:

+$258,865,234 Streets and San Total budget

- $156,645,516 Less Solid waste (but including street sweeping)

+$598,286,287 CDoT Total budget

-$206,643,000 Less Bike, Transit, Pedestrian improvements

$493,863,005 Total Auto spending

Income:

$99,100,000 State MFT

$205,100,000 Vehicle tax(Sticker, towing, impound)

$188,000,000 Transportation taxes (City MFT, Garage, Taxi)

$6,400,000 Motor Vehicle Lessor Tax

$4,100,000 Municipal auto rental tax

$6,400,000 Municipal Parking

$256,000,000 Fines, Forfeitures, Penalties (auto related)

$298,800,000 Infrastructure Grants (sourced from Fed or State MFT)

$1,063,900,000 Total Income

$570,037,000 Profit

Just for perspective, top income sources listed in the Budget are:

$1,299,000,000 Airports

$1,150,400,000 Water and Sewer

$831,500,000 Property Tax Levy

So, the gross revenues collected, make the auto-mobile Chicago's 3rd highest income generator and the profits are on par with the $647,900,000 the city hopes to receive from its share of the State and local Sales taxes.

Paul K. Dickman

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

NIMBY Cronicles 2, What happened to all the parking?

I moved into Wicker

Park

Nowadays, if I park closer than a block away, it’s a good

day.

Like most folks, I blamed the new development. It seemed a

good bet. After all, I was standing on the corner at ground zero when the condo

bomb went off, All the vacant lots were filled with infill construction, the

factories had been turned into loftominiums. North Ave. used to look like

Armitage, dotted with single family and small commercial. Now it is lined with

four story buildings. Like most folks, I figured that the increased

population used up all of the parking

spots.

Then I read a three part article in The Straight Dope by Ed

Zotti, called “Where everybody went”

He had crunched the data from the 2010 census and produced a

bunch of maps showing demographic shifts throughout the city.

In part three he had a map showing the change in housing

units from 1970 to 2010.

I was squinting at the map, trying to pick out my census

tract when I realized something.

Despite my impression of massive development, the number of

housing units in Wicker park was pretty much the same as it was in 1970. I went

back to part one and looked at the population density in 1980 and 2010 and

again I was surprised. The population here is about the same as it was when I

got here.

I was still incredulous, and looked at the census data

myself. It was true. Here are a couple of graphs I produced from the data for

the 8 census tracts that make up Wicker

Park

So where have all the cars come from? This is a problem 24

hours a day. They can’t all be day trippers and barflies?

Here’s another graph from 1970 to 2010 stacking the count of resident’s cars

over the number of dwelling units.

The answer is clear. We don’t have too many people, we have

too many cars.

And look at the timeline, this isn't some fallout from the

postwar car culture, this is a pile of buffalo chips we dragged in our shoes.

We tried mandating minimum parking ratios for new

construction.

Here’s a graph of our worst tract.

This tract has

probably the highest off street parking ratio in the neighborhood.

Only 5% of the units are in historic buildings with no

parking, 15% are in single family homes with 2 car garages and fully 75% of the

housing was built after 1990 and has a mandated 1-1 parking minimum. Despite an average

parking ratio of at least 1.1 the automobile ratio is 1.3. And judging by the street parking at least

half of the people are using their garages to store lawn furniture

I have come to the conclusion that cars are like goldfish. If

you keep feeding them, they will grow until they fill the bowl.

Neighborhoods are funny things, when they stop growing, they

start dying.

We have reached a point where the parking situation is

strangling our growth.

That is why I am flexible about reduced parking ratios.

We haven’t room for any more cars.

Paul K. Dickman

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)