Two flats

A curious thing about the 1957 zoning code is that it pretty

much made it impossible to build a two flat on a standard city lot. I have

always wondered about it. I’ve never heard anyone complain about them. The

previous code had duplex districts where such things were a matter of right.

The 57 map replaced them with R3 districts. But the text precluded

putting a two dwelling structure on one lot in those districts.

The standard city lot is 25x 125 to 25x150 or 3125 to 3500

square feet.

The Code controlled density by limiting the number of

dwelling units by the square footage of the lot.

In the case of R3 it was 2200 sq ft of lot area per dwelling

unit. As you can see, in order to build a two flat you would have to combine

two standard lots. Why would you bother? Why not just build two single family

homes?

The new code also defined the minimum lot size for each

district. I have always wondered about this as well, I mean the city was 95%

subdivided by 1957. Why would anyone think it was an issue?

As I researched these articles, I could find no enmity to

this humble dwelling. In fact I found quite the opposite. The Master plan of

residential land use of Chicago clearly stated that they expected 25%-35% of the city’s population to reside in “Two

family dwellings”.

Why were these excluded from the 1957 code? Was this just

some typo that followed us to this day?

Then I read “Building new Neighborhoods; subdivision design

and standards, 1943”.

And it became clear.

They intended to change the size of the

standard city lot.

Actually, they hoped to re-plat the bulk of the city

In their opinion 25 ft lots were too narrow, 35 ft was

marginal, 40-50 ft was preferred.

A 35x150 lot has 5250 sqft more than enough for two

dwellings.

“How’s that supposed to work.? Wouldn’t a 35ft lot line be

in the middle of someone else’s house?” you might ask.

Not if you tear them all down.

They write:

“REDEVELOPMENT OF OLD CHICAGO

The recommendations contained herein

pertaining to subdivision design and standards would apply not only to the land

now vacant but to the redevelopment of the 23 square miles of blighted and

near-blighted properties which must be rebuilt within the next generation. Thus

more than 41 square miles of land in the city would benefit from improved

standards of design and from practical specifications for residential land

improvements. Within these 41 square miles over 300,000 families could find new

home sites located in well-designed, attractive neighborhoods of good character

and environment.”

Still, that’s only 20% of the city.

In the Master Plan they defined the areas of the city as:

14.60% Blighted & Near blighted

36.31% Conservation

23.34% Stable

the remainder was either vacant or under going some kind of

development

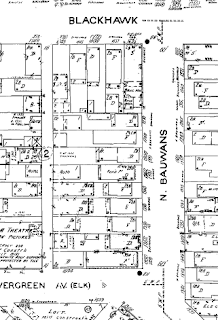

You can see them in this map.

Notice that the only areas they have marked as “Stable” are

out in the “Bungalow Belt” where the lots are already wide.

They figured that by the time they dealt with the blight,

the “Conservation” areas would now be blighted, either through decay or by

contrast with the “Rebuilt” areas. And then they would redevelop those.

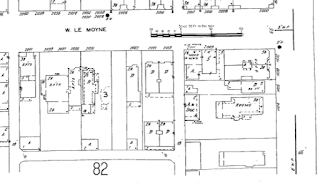

Here’s another map of future development areas.

Notice that the areas formerly tagged as “Conservation” are

now labeled “Ripe for rebuilding”

And the former “Stable” areas, now they’re tagged as “Conservation”.

Since the

future solvency and livability of our great cities depend upon removing the

cancerous blighted areas that are sapping their vitality and upon building new

model communities on the cleared sites, every device, legal and financial,

should be employed to make it economically feasible for the blighted areas to

be rebuilt by private enterprise.

The scope of this is staggering. They fully intended that

the normal process of future development, would involve taking property through

eminent domain, clearing it at government expense and redistributing it to some

connected developer who build only what the Plan Commission liked.

Luckily, this did not come to pass, but as casualty of

battle, the two flat was lost.

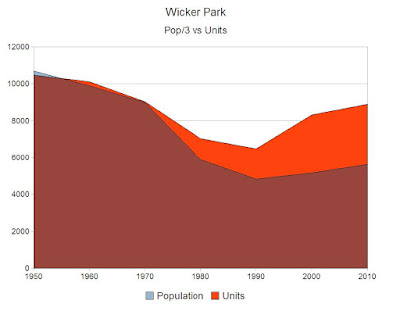

It needn’t be permanent though. You need only change one

character of the current zoning code to make these “as of right” in RS3 districts.

Change the Minimum Lot Area per Unit Standard for RS3 from 2500 to

1500.

This would double

the population density potential of about half the city and hopefully spur

development out in the neighborhoods where it’s needed.

Paul K. Dickman

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/09/make-no-small-plans-5-we-dont-want.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-4-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-3-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/08/make-no-little-plans-2-if-at-first-you.html

http://wickerblather.blogspot.com/2015/07/make-no-little-plans.html

These maps are courtesy of the Hathitrust Digital library, they were digitized by Google from originals in the

University of Michigan collection